Books: Book(s) you are Currently Reading | Part 3

- Thread starter GKJ

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

EXTRAS

Registered User

- Jul 31, 2012

- 9,010

- 6,465

Just read invisible cities by italo calvino and it reminded me of Pedro Paramo in that it kinda separates itself from time and space. At times I wanted to give it 1 star and at times 5 stars. Not the greatest writing but certainly interesting concept. Would recommend.

Also read Amok by Stefan Zweig and this was really great. Reminded me of dostoyevskys notes from underground. A man wanting to be good but ultimately self ruins and we get to watch that decay. can't wait to read the royal game by zweig soon.

Also read Amok by Stefan Zweig and this was really great. Reminded me of dostoyevskys notes from underground. A man wanting to be good but ultimately self ruins and we get to watch that decay. can't wait to read the royal game by zweig soon.

Babe Ruth

Proud member of the precariat working class.

- Feb 2, 2016

- 1,409

- 738

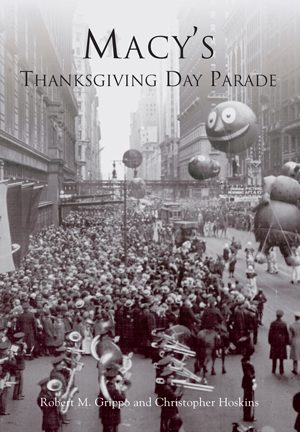

I've always liked the Macy's parade, so thought this might be a cool history. Book has a lot of photos & print ads from its early days in the '20s.

In the parade's first couple years, they would release the giant balloons after the parade route was finished.. but that practice had to be scrapped after the balloons interfered with air travel over NY. Funny..

Spring in Fialta

A malign star kept him

Just read invisible cities by italo calvino and it reminded me of Pedro Paramo in that it kinda separates itself from time and space. At times I wanted to give it 1 star and at times 5 stars. Not the greatest writing but certainly interesting concept. Would recommend.

Also read Amok by Stefan Zweig and this was really great. Reminded me of dostoyevskys notes from underground. A man wanting to be good but ultimately self ruins and we get to watch that decay. can't wait to read the royal game by zweig soon.

The Royal Game is such a great book.

BigBadBruins7708

Registered User

'Cinema Speculation' by Quentin Tarantino

Great read for anyone who loves movies or likes Tarantino. Basically you are getting his train of thought in book form about all of cinema, things he likes, dislikes, history, influences, etc.

Great read for anyone who loves movies or likes Tarantino. Basically you are getting his train of thought in book form about all of cinema, things he likes, dislikes, history, influences, etc.

Spring in Fialta

A malign star kept him

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

Any thoughts on this one so far?

Hey sorry for the late reply. I don't log on to this site as much anymore since the baby came along.

The book was made up of , I think, 4 essays - 2 of them were excellent , 2 were a chore . The good essays were - discourse on metaphysics & the mondology. You could probably find them for free online .

Babe Ruth

Proud member of the precariat working class.

- Feb 2, 2016

- 1,409

- 738

Congrats.. I've been missing your book posts.Hey sorry for the late reply. I don't log on to this site as much anymore since the baby came along.

Are you a first time father (?)

Re: your last post, Crime & Punishment was my favorite fiction for a long time. I also liked Notes.., House of the Dead, etc

Hippasus

1,9,45,165,495,1287,

No problem. Congratulations on your new child!Hey sorry for the late reply. I don't log on to this site as much anymore since the baby came along.

The book was made up of , I think, 4 essays - 2 of them were excellent , 2 were a chore . The good essays were - discourse on metaphysics & the mondology. You could probably find them for free online .

I see that Discourses in Metaphysics is a set of more general essays on metaphysics and theology, especially on god as necessary being and how perfection relates to him/her. I thought it might get more into his work on symbolic thought, formal logic, linear systems, geometry, calculus, or topology, but it seems not.

I'm going to read "The Monadology" soon.

Last edited:

frisco

Some people claim that there's a woman to blame...

Tarantino really liked Steve McQueen. Also, the section on Elvis was fascinating.'Cinema Speculation' by Quentin Tarantino

Great read for anyone who loves movies or likes Tarantino. Basically you are getting his train of thought in book form about all of cinema, things he likes, dislikes, history, influences, etc.

My Best-Carey

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

No problem. Congratulations on your new child!

I see that Discourses in Metaphysics is a set of more general essays on metaphysics and theology, especially on god as necessary being and how perfection relates to him/her. I thought it might get more into his work on symbolic thought, formal logic, linear systems, geometry, calculus, or topology, but it seems not.

I'm going to read "The Monadology" soon.

Yeah- the majority of the book was on theology and God.

Have you read Euclid - Elements ? Might be more of what you're looking for in relation to geometry , mathematics, etc.

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

Congrats.. I've been missing your book posts.

Are you a first time father (?)

Re: your last post, Crime & Punishment was my favorite fiction for a long time. I also liked Notes.., House of the Dead, etc

First time , yup! Busy busy ! You're a father , too, yeah?

I don't know why I've put off reading Crime and Punishment for so long - it's probably my favourite book I've read this year . So good!

Hippasus

1,9,45,165,495,1287,

I started God Created the Integers some time ago. This is an anthology in chronological order and excerpts from Euclid's Elements comprise the first section, but I'm reading it in reverse-chronological order. It is a great book so far, but super-hard. It'll probably take me years to still finish.Yeah- the majority of the book was on theology and God.

Have you read Euclid - Elements ? Might be more of what you're looking for in relation to geometry , mathematics, etc.

I just finished reading "The Monadology". It is very good, but I'm skeptical of how these monads can be apprehended by the author. They seem to fulfill a role like spirit or soul as a sort of building block of the universe. To some degree, Leibniz is a rationalist in the tradition of Descartes. Descartes has a mind-body dualism whilst Leibniz is trying to account for greater pluralism and the complexity of the universe with his notion of monads.

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

I started God Created the Integers some time ago. This is an anthology in chronological order and excerpts from Euclid's Elements comprise the first section, but I'm reading it in reverse-chronological order. It is a great book so far, but super-hard. It'll probably take me years to still finish.

I just finished reading "The Monadology". It is very good, but I'm skeptical of how these monads can be apprehended by the author. They seem to fulfill a role like spirit or soul as a sort of building block of the universe. To some degree, Leibniz is a rationalist in the tradition of Descartes. Descartes has a mind-body dualism whilst Leibniz is trying to account for greater pluralism and the complexity of the universe with his notion of monads.

I connected more with Descartes than Leibniz. Are you reading these for school or for fun ?

Crime and Punishment is the best fiction book I've read in a long, long time. Best since "Lonesome Dove" and I would put C&P above Lonesome Dove.

I'll be thinking of that book for a long time. Such a deep, profound psychological exploration of the human psyche , and humanity as a whole.

10/10

Hippasus

1,9,45,165,495,1287,

More for fun.I connected more with Descartes than Leibniz. Are you reading these for school or for fun ?

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

More for fun.

Awesome . I stumbled upon the classics as a happy accident - my life has changed for the better because of them.

Hockey Outsider

Registered User

- Jan 16, 2005

- 9,275

- 17,471

"Meditations" (Marcus Aurelius c. 180 – translation & intro by Gregory Hays, 2002)

Marcus Aurelius was a Roman emperor. He reigned from 161 to 180 (AD). During the final decade of his life, he wrote an untitled series of self-reflections. Essentially, the text documents Marcus's attempts to understand how to live a good life. Scholars generally believe that he never intended to publish his writing. It's unclear how the journals (subsequently named the "Meditations") survived the centuries.

Structurally, the Meditations consists of twelve books. In the first volume, Marcus summarizes the key lessons he's learned from his family, teachers, and peers. The longest entry is about his adopted father Antoninus Pius (there's another lengthy entry praising him in the sixth book). The remaining eleven journals don't appear to have any specific order (either in terms of how those eleven volumes should be arranged, or how the entries within each are organized). The meditations range in length from a single sentence to several long paragraphs. The writing is concise (some entries are unintelligible), but the occasional nature analogies (about trees, rocks and rivers) are illuminating.

David Arthur Reese once wrote that Marcus's musings "are not, and do not claim to be, a work of original philosophy". I agree with that assessment. Marcus's writings are based upon Stoic philosophy, which had been created four hundred years before Marcus was born. These volumes contain little that hasn’t already covered by Stoic writers such as Seneca and (especially) Epictetus. Furthermore, there's relatively little philosophical analysis (where an argument is advanced, supported by logical reasoning). Instead, Marcus repeats a number of core themes, almost obsessively. He generally assumes (rather than attempts to prove) that the underlying premises are true.

Despite this not being a rigorous philosophical treatise, there's significant value in the “Meditations”. Marcus discusses a number of core themes in detail – cultivating indifference to things outside of one's power, being patient with other people (even when they cause harm), and always remembering the inevitability of death. It would be impossible to summarize the “Meditations” into a single concept, but perhaps the most prominent idea is self-control. Marcus argues that what happens in the world is objectively neither good nor bad, and that we have the power to choose how to react to external events. In Book 4, Marcus notes (in his typical spartan prose) that one can "Choose not to be harmed — and you won't feel harmed. Don't feel harmed — and you haven't been". I (and especially my wife) would be happier and more productive choosing not to react to things that aren't crucial towards achieving our goals. Understanding that is straightforward, but acting on it is far tougher.

Given Marcus's role as emperor, he strived to be surprisingly understanding towards people who caused him harm. In Book 7, he notes "When people injure you, ask yourself what good or harm they thought would come of it. If you understand that, you'll feel sympathy rather than outrage or anger". In Book 11, he notes that if someone despises him, his role is "to be patient and cheerful", and to be "ready to show them their mistake. Not spitefully... but in an honest, upright way". Perhaps I'm cynical, but I have a hard time imagining most modern politicians being so magnanimous.

Although "Meditations" was written eighteen centuries ago, it's remarkable how current the text feels. At the start of the fifth book, Marcus talks about having trouble getting out of bed in the morning. I can't imagine any person who doesn't have these feelings, at least occasionally. He also criticizes the "despicable phoniness" of people who go out of their way to tell you that they're being honest (Book 11). I sometimes do that, and I should excise phrases like that from my vocabulary. As Marcus notes, your honesty "should be obvious — written in block letters on your forehead".

Some critics argue that Marcus's philosophy is a defensive one, which I agree with it. Although it provides considerable guidance on enduring hardships, there's no allowance for happiness. I also struggle with the concept of the "logos" (the pervasive force that gives order to the universe). It seems to be similar to the concept of "faith". I'm not sure how we can reconcile the concept of free will with a power that organizes the world. I could accept "logos" as, essentially, a code of conduct, under which people should be, among other things, honest and kind. Under this framework, people should be praised for following the guidelines, and criticized for not, but they're still free to choose. Marcus seems to take the concept much farther, and suggests that the logos is a physical force, that, among other things, absorbs the souls of the dead (Book 4).

Marcus frequently talked about the shortness of life, and how people are soon forgotten. He would likely be shocked and humbled that his self-reflections have survived for nearly two millennium. There's significant wisdom in these writings. Although many of the concepts are fairly simple, Marcus's repeated efforts to examine the same ideas from different perspectives help reinforce the lessons. Applying even a few of the lessons from “Meditations” would surely enrich anyone’s life.

(NOTE – I read the 2002 edition, translated by Gregory Hays. It also includes a helpful introduction about Marcus’s life, along with the historical and philosophical context of his writings).

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

Picked up and started reading yesterday, will miss new works from him now that he has passed, this was his last completed novel which makes me wonder if he had another that was not and if the estate will hire someone to complete it like sometimes happens after an authors death.

Babe Ruth

Proud member of the precariat working class.

- Feb 2, 2016

- 1,409

- 738

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

This sounds good. Let us know .

The waning optimism of America's middle-class citizenry..

Thucydides

Registered User

- Dec 24, 2009

- 8,161

- 878

Babe Ruth

Proud member of the precariat working class.

- Feb 2, 2016

- 1,409

- 738

It's pretty good. I know the sky is falling predictions get old, & lose credibility, after so many generations.. but i think it's becoming plainly obvious to an increasing number of people, America (& its empire) is in decline.This sounds good. Let us know .

This book is a relatively objective (& concerned) diagnosis for America's working & middle classes.

One of its strengths: Hanson's insight in to how modern technology & creature comforts are hiding decline. Basically, it's easier & less painful to lose political power & economic clout now, because it's less noticeable with so many accessible toys & distractions. But declining birth rates, declining home ownership rates, more government dependence, reveal the true middle/working class' decline in health. And it's trending fairly consistent with previous, historical/societal collapses.

Supposedly the book has some practical, optimistic solutions, but haven't gotten to that part yet.

History of postpunk during the 1970s/ early 80s, one of the most influential periods of music imo

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)

Latest posts

-

Speculation: 2025 Trade/ Free Agency thread (Free Agency is July 1st) (27 Viewers)

- Latest: robbieboy3686

-

Prospect Info: Kirill Kudryavtsev, #208 Overall, 2022 NHL Draft (28 Viewers)

- Latest: ScoutyMcScoutface

-

Confirmed with Link: [ANA/PHI] Trevor Zegras for Ryan Poehling, 45th Overall and 2026 4th Round Pick (67 Viewers)

- Latest: Ducks DVM

-