Here’s an expanded post I made about

Vladimír Dzurilla in the preliminary.

How to rank him? Dzurilla’s

prime covers the 1965-1972 period (age 23-30). He’d be the most seeked out goaltender from North American scouts during this time.

Ján Starší (CSSR national team coach over the 1970s, 1980s):

“He was a goalie who was not falling which Canadian coaches wanted to see. He perfectly covered the angles which means his spacial awareness and anticipation was on high level and that’s why he easily moved, didn’t fall and he played, we could say, the Canadian style. For these reasons we might call him the greatest European goaltender in his time.”

Jozef Golonka (CSSR national team player and captain over the 1960s):

“Vlado could have stayed in Canada thousands of times. He had offers that no other could have dreamed of.”

A fan question in the TIP magazine 1971 and Dzurilla’s response:

“If you were to receive an offer to play for professional team of Montreal or Chicago, which one would you choose?”

“I have been given an offer for a few years now. But not from Montreal nor from Chicago, but from Toronto. Truthfully though, it’s pointless to think about it.”

Vladimír Dzurilla represented a direct opposite of Jiří Holeček in many aspects; stylistically and temperamentally. Having Dzurilla and Holeček as options contributed to a great reputation of Czechoslovak goalies at the time, and to a confidence the Czechoslovak hockey public had in their netminders.

While Holeček took his time to develop, Dzurilla’s talent was imminent. He

first played the Czechoslovak league game

in 1959-60 as a 17 y/o. He got into the National team next season in Nov. 1960 just after 9 league games he had played so far. Translated into the context of our time, teenage Dzurilla would have been highly touted 1st or 2nd round draft pick, while Holeček would have gone undrafted.

Arne Strömberg, Swedish national team coach after Dzurilla’s 1st international game (CSSR losing to Sweden 1:3):

“Within the losing team I liked the goalie the most.”

Dzurilla

would have started his international career at the

1962 WHC held in Colorado Springs, USA but for various reasons Eastern Bloc countries (USSR, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Romania) declined their participation. Thus Dzurilla’s first championship experience came a year later.

Dzurilla switched starts with other goalies in 1963 and 1964 but he became #1 at the

’65 WHC. He was both statistically and voting-

wise the best goalie of the championship.

World Championship 1965

1. Leif Holmqvist (SWE): 2 games / 0 goals allowed / 41 saves / 1.000

2. Vladimír Dzurilla (CSSR): 6 games / 6 goals allowed / 107 saves /

0.9469

3. Viktor Zinger (USSR): 2 games / 3 goals allowed / 42 saves / 0.9333

4. Ken Broderick (CAN): 5 games / 11 goals allowed / 127 saves / 0.9203

5. Peter Kolbe (E. GER): 5 games / 17 goals allowed / 181 saves / 0.9141

6. Viktor Konovalenko (USSR): 5 games / 10 goals allowed / 95 saves / 0.9048

7. Juhani Lahtinen (FIN): 6 games / 23 goals allowed / 193 saves / 0.8935

8. Urpo Ylönen (FIN): 1 game / 4 goals allowed / 27 saves / 0.8710

9. Kjell Svensson (SWE): 6 games / 17 goals allowed / 111 saves / 0.8672

10. Vladimír Nadrchal (CSSR): 2 games / 4 goals allowed / 26 saves / 0.8667

11. Tom Haugh (USA): 7 games / 44 goals allowed / 273 saves / 0.8612

12. Don Collins (CAN): 2 games / 10 goals allowed / 56 saves / 0.8485

13. Klaus Hirche (E. GER): 2 games / 16 goals allowed / 89 saves / 0.8476

14. Kåre Østensen (NOR): 6 games / 42 goals allowed / 211 saves / 0.8340

15. Thore Nilsen (NOR): 1 game / 14 goals allowed / 43 saves / 0.7544

IIHF Directoriate´s Best Goaltender: Vladimír Dzurilla

All-Star Team Voting: 1. Vladimír Dzurilla (36 votes), 2. Tom Haugh (6 votes), 3. Peter Kolbe (5 votes), 4. Ken Broderick (4 votes), 5. Juhani Lahtinen, Kjell Svensson (1 vote)

Dzurilla kept the good play throughout

1966 season but

failed in the very last game, the deciding gold-medal game of CSSR vs. Soviets. He was pulled after 5 minutes when he conceded 3 goals. Czechoslovaks were actually closer to gold before the game actually since Soviets had only tied with Sweden. CSSR only needed a tie to come up first. If not for the last game, the competition for the best goalie awards might have been a close call between Dzurilla and Martin. Due to last game though, voters went for default choice and selected Martin.

Post 1966 WHC commentaries noted that Dzurilla relies on his good reflexes and cutting down shooter’s angle too much that it can undo all the good he brings. Faster leg mobility and better skating needs an improvement in order to stop his weakness – on-ice goals or goals slightly above the ice that should be blocked by legs. However, writers did not that

“quick puck distribution by a goalie stick to start a counterattack is perfectly controlled and used only by Dzurilla and there is no sight of applying this useful element by any other goalie.”

Dzurilla was a unicorn in the ranks of European goalies when it came to

stickhandling. Euro goalies were typically forced to stay deep in the crease and even actively discouraged to handle the puck by their coaches. Dzurilla was noted to record an assist in a league game for example. This was sometimes mentioned as an usual feat.

Stickhandling was a part of his aggressive, and sometimes

overly aggresssive style, challenging and pressuring the opposing players as much as he can. Dzurilla was loud and expressive verbally, shouting at forwards to throw them off. The other side of the coin was that he himself could have been caught out of position, to skate against forward too far out or to let himself be provoked and out of focus.

All of this dynamics is still present with Dzurilla at his veteran stage of career. Canada Cup games as well as 1977 WHC games. Take a look at what nearly 35 y/o goalie allows himself to do in a gold-medal deciding game, in the 3rd period after Czechoslovakia started off 4:0, and Soviets almost equaling the score. The game did end 4:3 in favor of CSSR and they won the gold medal. From today’s perspective I think Dzurilla looks good there, certainly entertaining, effectively creating a chance for his forward; though from a stereotypical European coach of the era this was unnecessarily risky play. Time of the video should be around 1:28:30.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5rHZF9J7jbU#t=88m20s

Meanwhile Jiří Holeček’s response after end of ‘78 Championship to the question:

“What is your opinion on Canadian goaltenders?”

JH:

“The best of them are equal to the European goalies. Moreover, they’re great in a good work with the hockey stick, in a quick pass release. I’ve never learnt that because since youth, coaches rather forced me to play safe.”

Vladimír

missed most of 1967 season due to knee injury and subsequent meniscus surgery. Dzurilla did return few weeks before the championship, but seen as unplayed, coaches took young Holeček and Nadrchal for the tournament. Meanwhile Canadian team had an exhibition game against Slovan Bratislava (1:1) couple days before the tournament. Dzurilla was the star of that game, calling into question the decision to leave him off.

Dissapointing 4th place finish of the team at 1967 WHC made it easy for Dzurilla to regain his status, even in spite of suffering another knee injury at the first league game of the

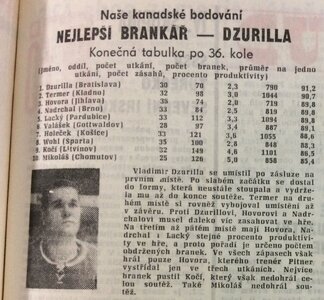

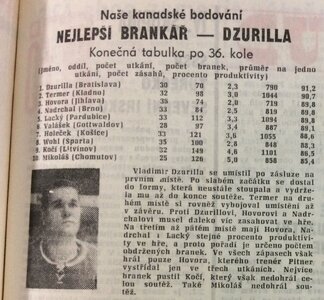

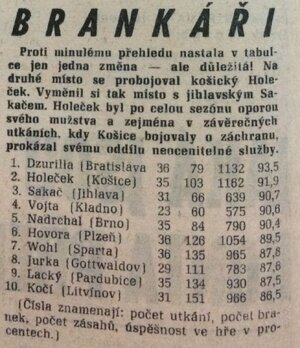

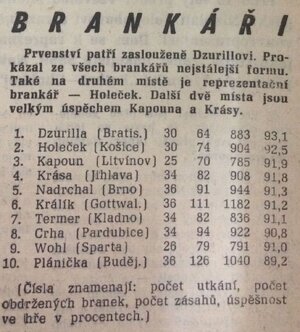

1968 season. Fortunately it didn’t require another surgery, he got back in time for the Olympics. He became a clear best Czechoslovak goalie again. Dzurilla didn’t shine statistically (0.873 in 7 games) but got a lot of praise including 5:4 win over Soviets. Dzurilla also had a comfortable lead in league SV%, finishing with 0.912 (91,2% on the picture below) when just one other starter had an SV% above 0.900.

His play continued to improve as he

became one of the top European players through 1969. Won both politically charged games against the USSR. Dzurilla ended the 1st encounter with a shutout which I believe hadn’t happened before. Soviets scored (even if they lost) in every game against a European opponent in a major tournament between 1954-1968.

The games at this championship has made Dzurilla a celebrity – to the fans of Czech and Slovak hockey. Not really the Canada Cup games, although his performance there has been also frequently reminded.

Despite my description, I don't want to single out Dzurilla as the finest netminder. 1969 WHC was a close call between Dzurilla and Holmqvist.

World Championship 1969

1. Miroslav Lacký (CSSR): 3 games / 2 goals allowed / 40 saves / 0.9524

2. Ken Dryden (CAN): 2 games / 3 goals allowed / 49 saves / 0.9423

3. Gunnar Bäckman (SWE): 2 games / 2 goals allowed / 29 saves / 0.9355

4. Vladimír Dzurilla (CSSR): 9 games / 18 goals allowed / 193 saves /

0.9147

5. Leif Holmqvist (SWE): 8 games / 17 goals allowed / 180 saves /

0.9137

6. Viktor Zinger (USSR): 10 games / 21 goals allowed / 200 saves / 0.9050

7. Wayne Stephenson (CAN): 8 games / 25 goals allowed / 228 saves / 0.9012

8. Urpo Ylönen (FIN): 10 games / 49 goals allowed / 301 saves / 0.8600

9. Mike Curran (USA): 10 games / 74 goals allowed / 442 saves / 0.8566

10. Lasse Kiili (FIN): 1 game / 3 goals allowed / 15 saves / 0.8333

11. Steve Rexe (CAN): 1 (?) game / 2 goals allowed / 8 saves / 0.8000

12. Viktor Puchkov (USSR): 1 (?) game / 2 goals allowed / 7 saves / 0.7778

IIHF Directoriate´s Best Goaltender: Leif Holmqvist

All-Star Team Voting: 1. Vladimír Dzurilla (59 votes out of 150 ballots), 2. Leif Holmqvist (56 votes), 3. Mike Curran (28 votes)

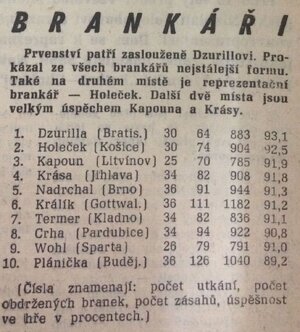

Dzurilla may have hit his peak during

1970. He played his best domestically, crushed his goalie competitors and was one of the main challengers to Jan Suchý placement in the Golden Stick voting. Dzurilla’s SV% lead (

0.935) over the others was quite something. See below the 1st column (games played), 2nd column (goals allowed), 3rd column (saves), and the last

4th column (SV%):

However, he faltered at the

’70 WHC. Dzurilla's performance was a

disappointment there as if he ran out of energy. His backup was injured so Dzurilla had to play all 10 anyway. So 1970 is a season difficult to evaluate in a sense that he was likely at his physical best but he wouldn’t do well in any kind post season all-European voting. To add some context, Leif Holmqvist won the Golden Puck award (Best Swedish player) and Viktor Konovalenko won the Soviet Best Player of the Year award. 1970 was pretty good season for European goalies.

Dzurilla

wasn’t a member of the National team over the course of

1971 season. There was a goalie controversy with the Slovan goalies Dzurilla and Marcel Sakáč, both regarded as national team calibre goalies, fighting each other in a one club. Slovan management got greedy, they didn’t want to let go either one for 3 years just because they feared how much they would improve the team to which they’d send off Sakáč or Dzurilla.

Sakáč played more in 1971 so he got to the National team, Dzurilla would play more for Slovan in 1972 so he was with the National team then.

So even though 1971 season isn’t valuable in terms of actual achievements (what happened on the ice), I’d be wary to write that off a signal of Dzurilla’s prime being lesser than the remaining 15 goalies this round. Sakáč played another World Championship 8 years later, right after Holeček and Dzurilla retired from serious hockey 1978 to finish off their careers in Germany. Sakáč was unlisted 3rd CSSR goalie at 1972, 1973 and 1977 championships. Sakáč would have likely been a regular goalie of any other European national team in the 1970s.

Dzurilla came back strong in

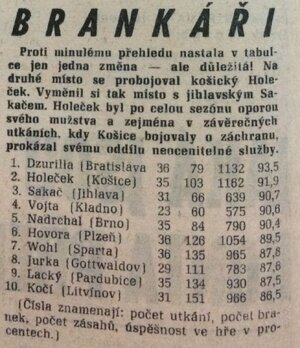

1972 and played more games than Holeček at the ’72 Olympics, stayed as a backup behind Holeček at the ’72 WHC two months later. Overall, Dzurilla was considered a bit better than Holeček in this season. Even with all the justified fame Holeček earned after golden 72 WHC, Dzurilla actually finished 3rd in a domestic GS voting; Holeček ended 5th. He had a very good domestic season again (leading

0.931 SV%):

Dzurilla turned 30 in

1972-1973 season. 3-year tension between the two goalies and management culminated into an open conflict when both goalies stood up and said: "Pick one of us, or we won´t play." But since the clubs in CSSR at the time had full control over players transfers, it hardly did anything.

An article by Ivan Ďurišin in the TIP magazine mid-season:

"Slovan officials assumed that the problem is solved. Not even close, the issue is not solved to this day to satisfaction of both, as one and the other lost what they so much desired: the uniform of the National team. One played, the other sat on the bench and secretly wished for the 'fall' of his comrade because he himself wanted to go on ice."

It was a fun media drama in its time. At one point the press reported that Dzurilla has enlisted himself to the army so that Dukla Jihlava (army team) would be entitled to draft him.

Dzurilla finally changed his club at the start of

1974 season. Everyone thought he’s

quitely closing off his career. In fact there was even a random fan question in the press around 74 or 75 directed at Karel Gut (CSSR coach) whether Dzurilla can return to the National team. Gut responded with a “no chance” quote and instead, the hockey association organized a retirement ceremony to Dzurilla in the mid-70s during one of national team exhibition games…

This is written to provide context for his

1976 comeback and to properly frame Dzurilla’s career. He’s the 1960s and early 1970s goaltender who unexpectedly recorded the

league’s best SV% in the ’76 season narrowly over Holeček (0.924 to 0.923).

When Dzurilla boosted his reputation in front of NA audience at the Canada Cup, he was half a decade past his prime in an age where a good chunk of his former teammates had already an established coaching career.

Dzurilla was the starting goalkeeper of the Czechoslovak team when they won

1977 WHC gold medal. Finished 6th in the ’77 Golden Stick voting, and as the best Czechoslovak goalie one last time.

It would be interesting to find out more about Dzurilla’s resurgence. As he grew old, I wonder, he maybe polished his style. Maybe he put more structure into his venturing out of the crease… Or an alternative, more earthly explanation would be… better financial incentives: In 1976, a new industrial company became a sponsor of the Brno club that Dzurilla was playing for.

____________________________________________________________

In 1978, a former National team goalie (Vladimír Dvořáček) praised the, now 36 y/o goaltender, the most out of the league’s starters:

“Always delivers reliable performance, draws from his experience, excellent work with the stick, covering the space and glove saves.”

Some of other descriptions are as follows. Hockeyarchives.info:

„Calm and collected goaltender who played the angles well. Surprisingly quick reflexes despite his size. Good at using his stick.“

Karel Gut, CSSR coach in the 1970s, wrote in 1985:

“Outstanding goalie who earned admiration not just in Europe but also in Canada especially in the 1970s. Perfectly handled covering of the shooting angles, was successfully stopping breakaways of opponents. Quick reactions and stick work were his big assets. His robust constitution radiated an unprecedented calmness over the team.”

His competitor Holeček was all about the inner game. He had his rituals, didn’t talk much outside the rink, tried to memorize skating and shots of individual forwards, didn’t talk on the ice, all directed toward maximum concentration. Dzurilla needed to pump himself up, to get euphoric. Both of them took inspiration from Seth Martin, but Martin’s butterfly and effectiveness in blocking on-ice shots were suited for Holeček better. Dzurilla maintained his stand-up goaltending.

An interview with Jiří Holeček, published in Gól magazine, February 1994: "

You were the first one who introduced a butterfly positioning here. How much of a revolutionary new thing that was at the time?"

JH:

No. I only improved it and frequently used it. Otherwise I watched it from the Canadian goalie Seth Martin, who came by here in the sixties. Vlado Dzurilla started trying a butterfly after him, and then me. Since I have had a bit looser joints, I was good at it.

The book

Příběhy z hokejové branky ["Stories from hockey goal"] written by Jiří Koliš, published in 2002, described a butterfly evolution in the Holeček, Esposito, Dryden chapter:

"Hall's playing technique, completely common these days, was a real revolution in his time. Before it got 'the Butterfly' name, it used to be compared to splayed upside-down letter V. Hall's basic stance was in deep forward bend with knees closed to each other, but with skates widely spread out. It really could have reminded the upside-down 'V' looking from behind, although Hall´s new stance seemed to shooters skating forward as almost an impenetrable dam. But what was the most important, such style was exceedingly effective.

This revolutionary way of goaltending was brought to Europe by excellent American netminder Willard Ikola in the second half of the fifties. But only the Canadian goaltender of the team Trail Smoke Eaters and of the Canadian National Team, Seth Martin, who attended the World Championship six times, and was declared the best goaltender of the Championship four times, perfectly mastered the new style and made it widespread in Europe. Martin even tasted the NHL atmosphere at the end of his career - he joined the St. Louis Blues team in the 1967-68 for the thirty games of the regular season and for the two play-off games. No other than Glenn Hall was his goaltending partner.

Vlado Dzurilla tried as the first one here the butterfly position during his beginnings in the League and in the National Team. His attempts ended up with torn meniscus though. Such goaltending style wasn't suited for him. But the fifteen year-old schoolboy Jiří Holeček, who spent hours and hours observing the best ones every day at the World Championship in Prague 1959, should have shown in the next years, how the butterfly position can be effective.”

_____________________________________________________

Since the Golden Stick voting was launched in 1969, there is a lot of Dzurilla’s seasons not covered. Thus the GS doesn’t provide the picture we need. Overall, he has

8 relevant seasons in which he was either a weaker #1 goalie in Europe, or average #2, or a strong #3 goalie in Europe.

1965, 1966, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1972, 1976, 1977

Dzurilla has

greater longevity than most of his competitors during the time he played. He guarded the net in front of Sven Tumba Johansson when he dressed the National team uniforms 1st time in 1960 against Sweden. He got to watch generations of Soviet players beginning with Sologubov, ending with Fetisov in 1977. He led the SC Riesersee club to the German league championship in 1981.

What’s the downside? There are

some empty seasons within Dzurilla’s prime (1967, 1971) and some of his clutch performances (1969 WHC, or 1976 Canada Cup and 1977 WHC) are mitigated by a few poor games against top opponents (matches with Soviets at 1966 WHC or at Olympics 1972). His highs were not as great as those of Tretiak or Holeček.

…But we’re not comparing him with the two here… Dzurilla is arguably 3rd best non-NHL goaltender the Europe produced between the WW2 and fall of Iron Curtain.

Top 5 goalie this week.