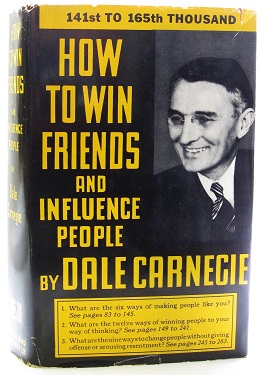

How to Win Friends and Influence People - Dale Carnegie (1936)

Was walking through Chapters, and saw this in the bargain area - I had heard about it a lot over the course of my life, so figured, why not?

It could also be titled

How to Win Friends by Being a Doormat

I can see how a lot of the tips of the book are applicable to people and society in 1936. Like those Time Magazine articles about how to be a woman on a date and make men like you.

To basically sum up entire book, here's how to make people like you!

1. Never argue even if they are wrong

2. Smile!

3. Try to figure out what the other party wants, and then work from that!

4. If all else fails - give in, people will like you if you give in to everything they want.

I honestly can't even see that working in the day of bored housewives and quotes from the Rockefellers, Lincolns and Roosevelts. Maybe in some circumstances but not as a life rule. And we now live in a 2017 society where commonality isn't something you should expect. People aren't polite in general and won't care if you are. We live in a world where a brash ***** grabbing dirtbag can be President of the United States - not Teddy Roosevelt.

Just for kicks, tonight I was out having beers by myself and decided, **** it, I'll just be the 1936 Dale Carnegie. Ask people about their lives, shake their hands, remember their names.

And of course people liked me. Common sense right? But in a Shaymalan twist, it worked out not just ok but great. People introduced me to their friends, "this is my new friend"..., I shook hands, heartedly like they were the most important person on earth as the book suggested - and everyone loved me.

I think there is great value to the book, but not in it's society of 1938 ways.

I'm interested to try it out again.

4/10

For now.