Pranzo Oltranzista

Registered User

- Oct 18, 2017

- 4,031

- 2,946

Decided to rewatch a few films. I know this thread will be even less popular than the one on the giallo, but thought they deserved to be linked and who knows, maybe others will add to it.

The panic movement emerged from the meeting in France of a bunch of young artists, among them Fernando Arrabal, a Spanish exile who fled the dictatorship of Franco, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Chilean, born of Jewish Russian immigrants, and Roland Topor, son of Polish Jewish refugees who had to hide in Savoie during the nazi occupation. All three had been victims or witnesses to some forms of social persecution, which could explain their interest for the surrealist group and its rejection of encompassing discourse and belief, be it political or religious, something that will remain at the center of their respective works. It is impossible to explain the artistic ambitions of the movement based on its manifesto or other writings from the artists – they claim that confusion and illogical reason are the core of the panic process and their explanations only exemplify these ideas (“panic is a way of life and not an artistic project”, “panic has never existed”) but, not unlike the surrealist movement of which it was born out, its reason-to-be is quite simple (I'll go into that in my comments below). Unsolvable quests, infinite wandering, absurd rituals are the main motifs of the narrative works associated to the movement, but it really was first actualized through artistic happenings such as the execution of live animals and other stunts* performed in order to break the distance between true experience and the comfort of simulation and representation – something that remains primordial in the execution of their (small but) unique body of films. For the panic artists, civilization (the main villain here) was a means for mankind to repress its true nature, and to simplify the true experience of reality – and their art was meant to liberate that experience, mainly using confusion (“Everything human is chaotic [confus]”). You can appreciate these films for their unmatched originality and uniqueness, for their mystical complexity, their political agenda, or their very peculiar continuity of surrealism, but the conscious work on their reception really is what makes them stand out. A psychoanalytical approach would have to consider abjection as the main effect to achieve that – years before Kristeva theorized the concept that would become central to the 80s gory films. I invite you to tread carefully in these parts, you are a target, and you might be triggered, if that's not your cup of piss, maybe watch something else.

Fando y Lis (Jodorowsky, 1968) – The premise could be straight out of mid-20s surrealism: in a post-apocalyptic world, where the bourgeois are content partying and dancing among the ruins, young lovers aspire to find a magical city where love and dreams are possible again. After the initial angry and anarchist reaction to WW1 of dadaism, surrealism came to be as an optimistic and mostly positive artistic movement. It emerges from the general agreement that the statue-quo was not sustainable, and that things needed to change in order to avoid future tragedies. Thinking outside the box by looking inside, letting your true self express itself and its needs (the artists often turning to psychoanalysis and different automatic-thoughts experiments or dream analysis), all that in order to come up with a better world (the bourgeoisie and the clergy where the first victims-to-be of this upgrade). The movement was cohesive and rather strong for 15 years, but took a fatal blow when WW2 was declared. There really was no need for it anymore, its ambition was a failure. Surrealism remained, as a style but not as a real movement, more and more predictable, and what was first an attack on bourgeoisie was recycled as an artistic refinement for the connaisseur. Jodorowsky's film departs very quickly from the original optimism of surrealism, and (just as the panic movement in general) its gloomy dark pessimism appears as a “we didn't do shit”, and the quest for the magical city is an impossible – and absurd – one. The film suffers from very limited means, and limited understanding of filmmaking (makes the chaos even more chaotic), but has a bunch of interesting ideas. It might not go as far as it should to really be effective as a panic film, but the idea of blurring the lines between representation and reality is absolutely there. The press kit for the film noted that "Every cinematographic trick was avoided. The actors, enduring a veritable 'Via Crucis,' were stripped naked, tortured and beaten. Artificial blood was never used." That's part of the panic movement modus operandi: the blurring of representation and reality was first pushed in through extreme imagery, but reinforced by the discourses surrounding the films (Jodorowsky famously said that he raped the actress for real in El Topo). Despite its sometimes clumsy construction, the film still feels relevant today, and feels like it has interesting things to say about different things (including abusive relationships, which was probably not Jodorowsky's intent). Like all of the following films, confusion is a main component, used mainly to force the spectator to try and understand what often seems indecipherable. 7/10

El Topo (Jodorowsky, 1970) – Certainly the closest to a genre film you'll find in this short list, El Topo is a panic western. It was John Lennon's favorite film of all times, Harrison and Yoko were big fans too (Lennon loved it so much that he got Allen Klein to produce The Holy Mountain and financed part of it), and the film certainly found its public and still has a huge cult following (Lynch, Refn, and so many others revere it). It is a perfect example of a panic film too, using the extreme to test the limits of representation and real, using confusion to force its viewer to really consider what's being told and shown to him. In an article about spirituality in Jodorowsky's films that has nothing to do with the panic process, Adam Breckenridge wrote: “[T]he film has its requisite deserts, outlaws, six shooters, cowboy hats and other staples of the western genre. But the bizarre imagery Jodorowsky surrounds them with often makes us hyper-aware of these images” [my emphasis]. And in relation to the panic rejection of encompassing discourses, Breckenridge also acknowledges that “in both films [El Topo and The Holy Mountain] Jodorowsky questions and undermines ideas of faith that were popular in the 1960s in complex and challenging ways” [my emphasis] and that even if (contrarily to the usual panic quest) the gunman manages to go through his absolutely absurd quest, his spiritual journey ultimately fails. Unlike Jodorowsky's two other panic films, El Topo pretty much stays away from political discourses, but it does a fine job at exposing the religious ones and most other beliefs as irrational (certainly surprising, in light of the later part of his career – but then again, he also said that “logic is stupidity”). It's a film that most people either love or hate. I'm somewhere in between. 7.5/10

Viva la Muerte (Arrabal, 1971) – Just like El Topo and The Holy Mountain, the film combines some extreme real visuals (bleeding a man with fire cupping after cutting his skin with a razor; cutting a living insect in two and filming one half trying to run away) with some scenes that make you question the morality of the filmmakers in other ways (the incestuous tension includes a scene where the boy – who must be around 10 y/o – whips his topless aunt). In both cases, the idea is to force the spectator to consider the work of art through its relation to reality (the young boy really did whip that woman, the insect really got cut in half), and per extension reengage art as a discourse capable of impacting reality. The panic movement appears in the dying breath of surrealism (officially declared dead in 1969, but irrelevant as a movement since 1940), from artists who deplore what it became: soft bourgeois amusement. It's still in continuity of surrealism and can't escape some of its reflexes (for example, the cynicism towards religion – the priest thanking God for the delicious meal after the kids feed him his own testicles is nothing short of amazing). Still, and just like Roland Topor, Arrabal couldn't stand André Breton and his rules (another rejection that is only coherent with the ideas of the panic movement**), and the break from surrealism was inevitable. Before The Holy Mountain, Arrabal uses here some more common forms of distanciation, through reflexivity (the boy throwing up on the lens of the camera, but also lots of weird visual effects and color saturation to picture the boy's musings, which are all pretty lame and disfigure an otherwise very good looking film). These effects also result in making some of the harder visuals difficult to see, making the film – at first – feel more prude, cautious or reasonable than the Jodorowsky ones, but it ends up going pretty far (the cow at the end should be enough to shock most viewers who made it that far). The film is adapted from an Arrabal novel and is partly inspired by his own childhood and the boy is clearly an avatar of the director (Fando/Fernando): his father was arrested when he was a child, condemned to death, attempted suicide, escaped from prison, all true – and clearly he also really blames his mother for handing his father to the authorities, which is also the main subject of his play The Two Executioners. These traumas, and Arrabal's political stance, also tainted Fando y Lis, to which Viva la Muerte alludes on its final scene, with Fando being pushed around on a cart by his girlfriend. Like the best films of Jodorowsky, it's a film that everybody should have seen, but that most people probably shouldn't watch. 8.5/10

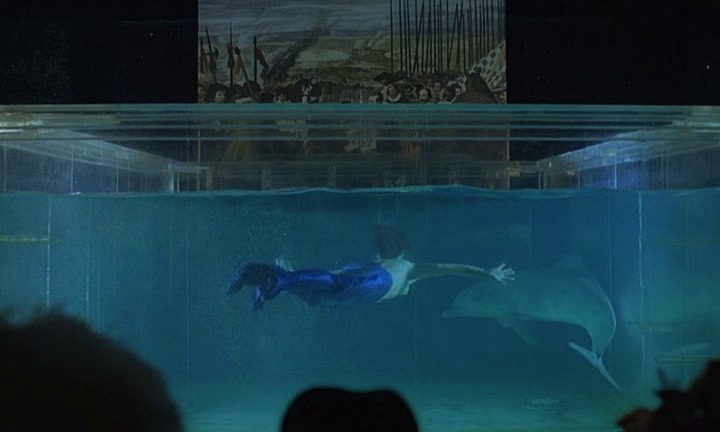

Holy Mountain (Jodorowsky, 1973) – I guess that if you have only one of the panic films to see, this is it. Everything panic is in there, and the film is gorgeous, from its imagery to its soundtrack (with Don Cherry – the jazzman – at the helm). It has some of the best visual ideas ever filmed, and had lasting influence on many great minds of cinema (including quite a few of my favorites, from Angelopoulos and Andersson, to Zulawski). The film's structure is absolutely unique – and if at first it seems like a political comment on Mexico's social climate (going back to a delirious recreation of the Spanish colonization with lizards and frogs – real amphibians and reptiles used in the most panic fashion), it quickly bursts into narrative vignettes that range from mystically absurd to batshit crazy. The series of portraits of the most powerful mortal people in the world is, for most of them, pure gold – and what was unfiltered tongue-in-cheek offense to the prude at the time feels strangely relevant today (and will still be offensive to the prude). Like the other panic films, it takes aim at political and religious encompassing discourses, at the bourgeois, the parvenu, and here more directly at the avant-garde art that's made to please them. Morally questionable images (a man taking his glass eye out of its socket and offering it to a child prostitute) and other moments of perceived reality punch again through Jodorowsky's fiction, but contrarily to the other films of the movement, it goes all the way and completely breaks immersion at the end. The process is somewhat conflicting with the panic usual process, reframing the work as a creation and as fiction, and thus reassessing its distance to reality. The ending dialogue (which really sounds like Zizek, in both tone and broken English – you suddenly feel like you're watching one of the talking points of The Pervert's Guide to Cinema) still implies that this distance between film and reality is superable and that one could reach the other: “Is this life reality? No, it is a film […] we are images, dreams […] we shall break the illusion”, and off they go, because real life awaits them. The cult leader abandons their quest for immortality, but by acknowledging their status as images, they actually reached it, the same way the characters of L'invenzione di Morel did. The whole thing breaks away from panic and feels more assumed and intentional as a postmodern work, but it only adds to the film's complexity and grandeur. 9.5/10

J'irai comme un cheval fou (I Will Walk Like a Crazy Horse, Arrabal, 1973) – This one didn't age as well as the others to me. Its mocking of civilization, of progress and of modern customs, in opposition to the primitive, the natural and the magical, feels a little forced (I love the title of the film, but nothing else really feels like a great idea). The rejection of any and all encompassing discourses is again at the center of the narrative, but maybe too clearly this time, and the result is not as effective (even clumsy at times, with poor execution in both directing and editing). Absurd rituals, confusion and pointless wandering are again the motors of the narrative, making it a very good example of panic works, but Arrabal is tamed here compared to his previous film – the incursion of reality and of real images is somewhat lost through the use of cheap effects, and the moral ambiguity of certain directorial choices are either repetitive (boy nudity) or look fake (penis torture). The result is just not the same. It still remains an anomaly in the spectrum of cinema, a film that couldn't be made today and that will bother most people who prefer their comfort not to be challenged. 5.5/10

That's it. As far as I know, that's every panic films. If you have anything more, I'm very much interested.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Some anecdotes:

* Certainly one of the most memorable of the panic happenings was performed in two parts by Diego Bardon, a toreador who was one of the few artists surrounding Arrabal, Topor and Jodorowsky (they were about 12). One day, in the arena, he refused to perform and kill the bull and fed it salad instead, causing a mini scandal. He then got invited by a group in favor of animal rights as an honorary guest, went to the event and instead of giving the grateful and motivational speech he was awaited for, he snapped the neck of a living chicken with his bare hands in front of the audience.

** Arrabal recalls: “We were very proud, we metics, him Mexican (Jodorowsky), and me Spanish, when Breton welcomed us [in the surrealist group] and kissed the hands of our wives, we thought we already had reach glory. There was a third person who was also invited, accepted, in this group, it was Topor. And you know, being accepted into the group was very difficult. And what did Topor do? He came, he saw, and once he understood that there was a baticanist side, a dogmatic side...after ten minutes, Topor asked, where are the washrooms? And he disappeared... So, he resisted the surrealist group, which was at that time an aspiration for every young artist, and a dream since it was very difficult to attain.”

---------------------------------------------------------------

Some adjacent films:

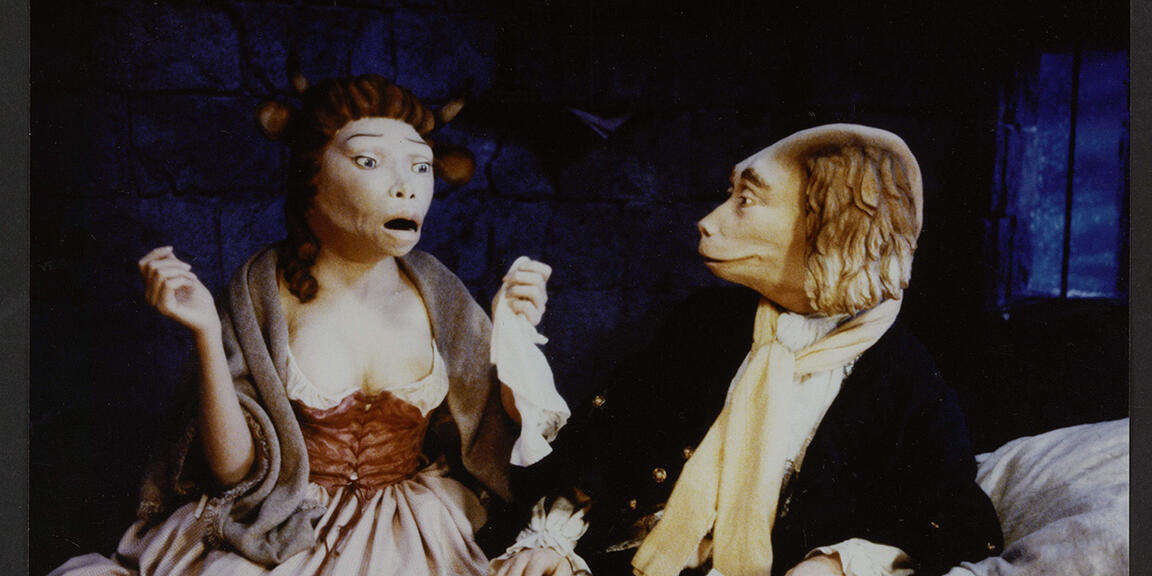

La cravate (Jodorowsky, 1957) – First short film by Jodorowsky (and friends), made a few years before the panic movement came to be. It hasn't much to do with what would follow, but it was good enough to impress the surrealists – Cocteau loved it. It's a mime film (Jodorowsky was a mime, a clown, a puppeteer and many other things before being a director, a poet, a comic book writer, etc.) about a guy who swaps his head for new ones to try to win the heart of a woman, but fails. His body then goes on a quest to find its old head, which the head-selling lady had kept in a jar on her fireplace. Jodorowsky said about the film: “You will be disappointed by it, because it was made by an amateur. I had no experience. Maybe that's good. I don't know. I'm not ashamed of how I did it. You can see I was already a director. It is well made. No money, but well made. It is good to finally have it. This picture was a fable done in mime.” The film was lost for 50 years and is pretty good for what it is. 4/10

La planète sauvage (Fantastic Planet, Laloux, 1973) – Adapted and partly animated by Roland Topor, I've seen a few sources suggesting it as part of the panic films, despite being an animated film (making it very difficult for some of the panic usual gimmicks to work – no real bits here to shock and suck you in). Lots of the main panic thematic elements are present, the absurdity, the rituals, and the opposition between civilized (domesticated) and natural that was central to Arrabal's film of the same year. Its quest do get resolved, but it's still pretty dark and gloom, with some bloody violence and nudity. The film got a Special Prize at Cannes. 4.5/10

L'arbre de Guernica (Arrabal, 1975) – An aristocrat wants his son to come back from his bohemian life and rule by his side in order to crush the people who wants the land to be owned by those who cultivates it. The son is part of a surrealist group (that just bears too many resemblance to the panic movement, their main activity being shocking happenings), and his answer to his father's offer is to jerk off and cum in his glass of wine. The film comes two years after the panic movement was abandoned, but reuses most of its elements. Arrabal employs a different and more common strategy to mix reality into his fiction, editing some archive war footage into the film, but maintains a few classic panic moments of blasphemous imagery, questionable morals, quasi-hardcore sex and (dwarf) violence. The only thing generally missing here is the confusion, as L'arbre de Guernica is a pretty straightforward film, in which even the wide and metaphorical rejection of encompassing discourses finds clear and concrete avenues: it's an anti-fascist and anti-christian film – joined through a passionate homosexual kiss, with the priest licking the fascist's face (Arrabal was always more to the point than Jodorowsky, but never that much). It is the most explicitly political of the films covered here, which is already saying a lot, but realism not being Arrabal's forte, it's not exactly working as a war film. I've read arguments for its inclusion as a panic film. I can't say I agree, but like some of what would come later from Jodorowsky, the lineage is obvious. 5/10

The Tenant (Polanski, 1976) – The film is an adaptation of a panic novel by Roland Topor. Aesthetically, it is miles away from the films of the movement, it's too a beautiful film, certainly better directed than most of the panic films, but it doesn't have that je-ne-sais-quoi that annihilates expectations and makes anything possible. It doesn't have the nerves, it doesn't have the rawness, and it doesn't have the scope. Don't get me wrong, it's an amazing film, it just have little to do with panic. One might consider it has a faint and punctual surrealist feel, and you could certainly point to its use of absurdity and confusion as traces of the panic process, but it's too controlled and tamed. That being said, I haven't read the book and the film is said to be as faithful as could be, so maybe literature ain't really much of a panic-friendly medium. It is clear from some excerpts, that Topor had the main character as a pure representation of what Arrabal called an “homme panique” (and I don't know how well you can translate these descriptions to images): “He was perfectly conscious of the absurdity of his behavior, but he was incapable of changing it. This absurdity was an essential part of him. It was probably the most basic element of his personality.” Still, lots of other things could be said about this great film and its amazing dark humor. If one would have to pick Polanski's best film, there's only one good answer and it's “any one of the apartment trilogy”. 9/10

I have a few adjacent films left to watch. I'll comment later. There's also a few I would have liked to find (but couldn't) and that are somewhat linked to the movement (most of them probably shouldn't be considered in the discussion, but I'd still be curious to see them): Un Alma Pura (1965), Le boucher, la star et l'orpheline (1975), The Orphan Girl Without An Arm (2011), and He! Viva Dada (1965), which is a documentary that includes works by panic artists. I'm also very interested by any other suggestion.

The panic movement emerged from the meeting in France of a bunch of young artists, among them Fernando Arrabal, a Spanish exile who fled the dictatorship of Franco, Alejandro Jodorowsky, Chilean, born of Jewish Russian immigrants, and Roland Topor, son of Polish Jewish refugees who had to hide in Savoie during the nazi occupation. All three had been victims or witnesses to some forms of social persecution, which could explain their interest for the surrealist group and its rejection of encompassing discourse and belief, be it political or religious, something that will remain at the center of their respective works. It is impossible to explain the artistic ambitions of the movement based on its manifesto or other writings from the artists – they claim that confusion and illogical reason are the core of the panic process and their explanations only exemplify these ideas (“panic is a way of life and not an artistic project”, “panic has never existed”) but, not unlike the surrealist movement of which it was born out, its reason-to-be is quite simple (I'll go into that in my comments below). Unsolvable quests, infinite wandering, absurd rituals are the main motifs of the narrative works associated to the movement, but it really was first actualized through artistic happenings such as the execution of live animals and other stunts* performed in order to break the distance between true experience and the comfort of simulation and representation – something that remains primordial in the execution of their (small but) unique body of films. For the panic artists, civilization (the main villain here) was a means for mankind to repress its true nature, and to simplify the true experience of reality – and their art was meant to liberate that experience, mainly using confusion (“Everything human is chaotic [confus]”). You can appreciate these films for their unmatched originality and uniqueness, for their mystical complexity, their political agenda, or their very peculiar continuity of surrealism, but the conscious work on their reception really is what makes them stand out. A psychoanalytical approach would have to consider abjection as the main effect to achieve that – years before Kristeva theorized the concept that would become central to the 80s gory films. I invite you to tread carefully in these parts, you are a target, and you might be triggered, if that's not your cup of piss, maybe watch something else.

Fando y Lis (Jodorowsky, 1968) – The premise could be straight out of mid-20s surrealism: in a post-apocalyptic world, where the bourgeois are content partying and dancing among the ruins, young lovers aspire to find a magical city where love and dreams are possible again. After the initial angry and anarchist reaction to WW1 of dadaism, surrealism came to be as an optimistic and mostly positive artistic movement. It emerges from the general agreement that the statue-quo was not sustainable, and that things needed to change in order to avoid future tragedies. Thinking outside the box by looking inside, letting your true self express itself and its needs (the artists often turning to psychoanalysis and different automatic-thoughts experiments or dream analysis), all that in order to come up with a better world (the bourgeoisie and the clergy where the first victims-to-be of this upgrade). The movement was cohesive and rather strong for 15 years, but took a fatal blow when WW2 was declared. There really was no need for it anymore, its ambition was a failure. Surrealism remained, as a style but not as a real movement, more and more predictable, and what was first an attack on bourgeoisie was recycled as an artistic refinement for the connaisseur. Jodorowsky's film departs very quickly from the original optimism of surrealism, and (just as the panic movement in general) its gloomy dark pessimism appears as a “we didn't do shit”, and the quest for the magical city is an impossible – and absurd – one. The film suffers from very limited means, and limited understanding of filmmaking (makes the chaos even more chaotic), but has a bunch of interesting ideas. It might not go as far as it should to really be effective as a panic film, but the idea of blurring the lines between representation and reality is absolutely there. The press kit for the film noted that "Every cinematographic trick was avoided. The actors, enduring a veritable 'Via Crucis,' were stripped naked, tortured and beaten. Artificial blood was never used." That's part of the panic movement modus operandi: the blurring of representation and reality was first pushed in through extreme imagery, but reinforced by the discourses surrounding the films (Jodorowsky famously said that he raped the actress for real in El Topo). Despite its sometimes clumsy construction, the film still feels relevant today, and feels like it has interesting things to say about different things (including abusive relationships, which was probably not Jodorowsky's intent). Like all of the following films, confusion is a main component, used mainly to force the spectator to try and understand what often seems indecipherable. 7/10

El Topo (Jodorowsky, 1970) – Certainly the closest to a genre film you'll find in this short list, El Topo is a panic western. It was John Lennon's favorite film of all times, Harrison and Yoko were big fans too (Lennon loved it so much that he got Allen Klein to produce The Holy Mountain and financed part of it), and the film certainly found its public and still has a huge cult following (Lynch, Refn, and so many others revere it). It is a perfect example of a panic film too, using the extreme to test the limits of representation and real, using confusion to force its viewer to really consider what's being told and shown to him. In an article about spirituality in Jodorowsky's films that has nothing to do with the panic process, Adam Breckenridge wrote: “[T]he film has its requisite deserts, outlaws, six shooters, cowboy hats and other staples of the western genre. But the bizarre imagery Jodorowsky surrounds them with often makes us hyper-aware of these images” [my emphasis]. And in relation to the panic rejection of encompassing discourses, Breckenridge also acknowledges that “in both films [El Topo and The Holy Mountain] Jodorowsky questions and undermines ideas of faith that were popular in the 1960s in complex and challenging ways” [my emphasis] and that even if (contrarily to the usual panic quest) the gunman manages to go through his absolutely absurd quest, his spiritual journey ultimately fails. Unlike Jodorowsky's two other panic films, El Topo pretty much stays away from political discourses, but it does a fine job at exposing the religious ones and most other beliefs as irrational (certainly surprising, in light of the later part of his career – but then again, he also said that “logic is stupidity”). It's a film that most people either love or hate. I'm somewhere in between. 7.5/10

Viva la Muerte (Arrabal, 1971) – Just like El Topo and The Holy Mountain, the film combines some extreme real visuals (bleeding a man with fire cupping after cutting his skin with a razor; cutting a living insect in two and filming one half trying to run away) with some scenes that make you question the morality of the filmmakers in other ways (the incestuous tension includes a scene where the boy – who must be around 10 y/o – whips his topless aunt). In both cases, the idea is to force the spectator to consider the work of art through its relation to reality (the young boy really did whip that woman, the insect really got cut in half), and per extension reengage art as a discourse capable of impacting reality. The panic movement appears in the dying breath of surrealism (officially declared dead in 1969, but irrelevant as a movement since 1940), from artists who deplore what it became: soft bourgeois amusement. It's still in continuity of surrealism and can't escape some of its reflexes (for example, the cynicism towards religion – the priest thanking God for the delicious meal after the kids feed him his own testicles is nothing short of amazing). Still, and just like Roland Topor, Arrabal couldn't stand André Breton and his rules (another rejection that is only coherent with the ideas of the panic movement**), and the break from surrealism was inevitable. Before The Holy Mountain, Arrabal uses here some more common forms of distanciation, through reflexivity (the boy throwing up on the lens of the camera, but also lots of weird visual effects and color saturation to picture the boy's musings, which are all pretty lame and disfigure an otherwise very good looking film). These effects also result in making some of the harder visuals difficult to see, making the film – at first – feel more prude, cautious or reasonable than the Jodorowsky ones, but it ends up going pretty far (the cow at the end should be enough to shock most viewers who made it that far). The film is adapted from an Arrabal novel and is partly inspired by his own childhood and the boy is clearly an avatar of the director (Fando/Fernando): his father was arrested when he was a child, condemned to death, attempted suicide, escaped from prison, all true – and clearly he also really blames his mother for handing his father to the authorities, which is also the main subject of his play The Two Executioners. These traumas, and Arrabal's political stance, also tainted Fando y Lis, to which Viva la Muerte alludes on its final scene, with Fando being pushed around on a cart by his girlfriend. Like the best films of Jodorowsky, it's a film that everybody should have seen, but that most people probably shouldn't watch. 8.5/10

Holy Mountain (Jodorowsky, 1973) – I guess that if you have only one of the panic films to see, this is it. Everything panic is in there, and the film is gorgeous, from its imagery to its soundtrack (with Don Cherry – the jazzman – at the helm). It has some of the best visual ideas ever filmed, and had lasting influence on many great minds of cinema (including quite a few of my favorites, from Angelopoulos and Andersson, to Zulawski). The film's structure is absolutely unique – and if at first it seems like a political comment on Mexico's social climate (going back to a delirious recreation of the Spanish colonization with lizards and frogs – real amphibians and reptiles used in the most panic fashion), it quickly bursts into narrative vignettes that range from mystically absurd to batshit crazy. The series of portraits of the most powerful mortal people in the world is, for most of them, pure gold – and what was unfiltered tongue-in-cheek offense to the prude at the time feels strangely relevant today (and will still be offensive to the prude). Like the other panic films, it takes aim at political and religious encompassing discourses, at the bourgeois, the parvenu, and here more directly at the avant-garde art that's made to please them. Morally questionable images (a man taking his glass eye out of its socket and offering it to a child prostitute) and other moments of perceived reality punch again through Jodorowsky's fiction, but contrarily to the other films of the movement, it goes all the way and completely breaks immersion at the end. The process is somewhat conflicting with the panic usual process, reframing the work as a creation and as fiction, and thus reassessing its distance to reality. The ending dialogue (which really sounds like Zizek, in both tone and broken English – you suddenly feel like you're watching one of the talking points of The Pervert's Guide to Cinema) still implies that this distance between film and reality is superable and that one could reach the other: “Is this life reality? No, it is a film […] we are images, dreams […] we shall break the illusion”, and off they go, because real life awaits them. The cult leader abandons their quest for immortality, but by acknowledging their status as images, they actually reached it, the same way the characters of L'invenzione di Morel did. The whole thing breaks away from panic and feels more assumed and intentional as a postmodern work, but it only adds to the film's complexity and grandeur. 9.5/10

J'irai comme un cheval fou (I Will Walk Like a Crazy Horse, Arrabal, 1973) – This one didn't age as well as the others to me. Its mocking of civilization, of progress and of modern customs, in opposition to the primitive, the natural and the magical, feels a little forced (I love the title of the film, but nothing else really feels like a great idea). The rejection of any and all encompassing discourses is again at the center of the narrative, but maybe too clearly this time, and the result is not as effective (even clumsy at times, with poor execution in both directing and editing). Absurd rituals, confusion and pointless wandering are again the motors of the narrative, making it a very good example of panic works, but Arrabal is tamed here compared to his previous film – the incursion of reality and of real images is somewhat lost through the use of cheap effects, and the moral ambiguity of certain directorial choices are either repetitive (boy nudity) or look fake (penis torture). The result is just not the same. It still remains an anomaly in the spectrum of cinema, a film that couldn't be made today and that will bother most people who prefer their comfort not to be challenged. 5.5/10

That's it. As far as I know, that's every panic films. If you have anything more, I'm very much interested.

----------------------------------------------------------------

Some anecdotes:

* Certainly one of the most memorable of the panic happenings was performed in two parts by Diego Bardon, a toreador who was one of the few artists surrounding Arrabal, Topor and Jodorowsky (they were about 12). One day, in the arena, he refused to perform and kill the bull and fed it salad instead, causing a mini scandal. He then got invited by a group in favor of animal rights as an honorary guest, went to the event and instead of giving the grateful and motivational speech he was awaited for, he snapped the neck of a living chicken with his bare hands in front of the audience.

** Arrabal recalls: “We were very proud, we metics, him Mexican (Jodorowsky), and me Spanish, when Breton welcomed us [in the surrealist group] and kissed the hands of our wives, we thought we already had reach glory. There was a third person who was also invited, accepted, in this group, it was Topor. And you know, being accepted into the group was very difficult. And what did Topor do? He came, he saw, and once he understood that there was a baticanist side, a dogmatic side...after ten minutes, Topor asked, where are the washrooms? And he disappeared... So, he resisted the surrealist group, which was at that time an aspiration for every young artist, and a dream since it was very difficult to attain.”

---------------------------------------------------------------

Some adjacent films:

La cravate (Jodorowsky, 1957) – First short film by Jodorowsky (and friends), made a few years before the panic movement came to be. It hasn't much to do with what would follow, but it was good enough to impress the surrealists – Cocteau loved it. It's a mime film (Jodorowsky was a mime, a clown, a puppeteer and many other things before being a director, a poet, a comic book writer, etc.) about a guy who swaps his head for new ones to try to win the heart of a woman, but fails. His body then goes on a quest to find its old head, which the head-selling lady had kept in a jar on her fireplace. Jodorowsky said about the film: “You will be disappointed by it, because it was made by an amateur. I had no experience. Maybe that's good. I don't know. I'm not ashamed of how I did it. You can see I was already a director. It is well made. No money, but well made. It is good to finally have it. This picture was a fable done in mime.” The film was lost for 50 years and is pretty good for what it is. 4/10

La planète sauvage (Fantastic Planet, Laloux, 1973) – Adapted and partly animated by Roland Topor, I've seen a few sources suggesting it as part of the panic films, despite being an animated film (making it very difficult for some of the panic usual gimmicks to work – no real bits here to shock and suck you in). Lots of the main panic thematic elements are present, the absurdity, the rituals, and the opposition between civilized (domesticated) and natural that was central to Arrabal's film of the same year. Its quest do get resolved, but it's still pretty dark and gloom, with some bloody violence and nudity. The film got a Special Prize at Cannes. 4.5/10

L'arbre de Guernica (Arrabal, 1975) – An aristocrat wants his son to come back from his bohemian life and rule by his side in order to crush the people who wants the land to be owned by those who cultivates it. The son is part of a surrealist group (that just bears too many resemblance to the panic movement, their main activity being shocking happenings), and his answer to his father's offer is to jerk off and cum in his glass of wine. The film comes two years after the panic movement was abandoned, but reuses most of its elements. Arrabal employs a different and more common strategy to mix reality into his fiction, editing some archive war footage into the film, but maintains a few classic panic moments of blasphemous imagery, questionable morals, quasi-hardcore sex and (dwarf) violence. The only thing generally missing here is the confusion, as L'arbre de Guernica is a pretty straightforward film, in which even the wide and metaphorical rejection of encompassing discourses finds clear and concrete avenues: it's an anti-fascist and anti-christian film – joined through a passionate homosexual kiss, with the priest licking the fascist's face (Arrabal was always more to the point than Jodorowsky, but never that much). It is the most explicitly political of the films covered here, which is already saying a lot, but realism not being Arrabal's forte, it's not exactly working as a war film. I've read arguments for its inclusion as a panic film. I can't say I agree, but like some of what would come later from Jodorowsky, the lineage is obvious. 5/10

The Tenant (Polanski, 1976) – The film is an adaptation of a panic novel by Roland Topor. Aesthetically, it is miles away from the films of the movement, it's too a beautiful film, certainly better directed than most of the panic films, but it doesn't have that je-ne-sais-quoi that annihilates expectations and makes anything possible. It doesn't have the nerves, it doesn't have the rawness, and it doesn't have the scope. Don't get me wrong, it's an amazing film, it just have little to do with panic. One might consider it has a faint and punctual surrealist feel, and you could certainly point to its use of absurdity and confusion as traces of the panic process, but it's too controlled and tamed. That being said, I haven't read the book and the film is said to be as faithful as could be, so maybe literature ain't really much of a panic-friendly medium. It is clear from some excerpts, that Topor had the main character as a pure representation of what Arrabal called an “homme panique” (and I don't know how well you can translate these descriptions to images): “He was perfectly conscious of the absurdity of his behavior, but he was incapable of changing it. This absurdity was an essential part of him. It was probably the most basic element of his personality.” Still, lots of other things could be said about this great film and its amazing dark humor. If one would have to pick Polanski's best film, there's only one good answer and it's “any one of the apartment trilogy”. 9/10

I have a few adjacent films left to watch. I'll comment later. There's also a few I would have liked to find (but couldn't) and that are somewhat linked to the movement (most of them probably shouldn't be considered in the discussion, but I'd still be curious to see them): Un Alma Pura (1965), Le boucher, la star et l'orpheline (1975), The Orphan Girl Without An Arm (2011), and He! Viva Dada (1965), which is a documentary that includes works by panic artists. I'm also very interested by any other suggestion.