Hello everyone!

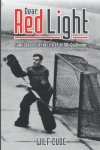

This week I'll be presenting my late friend Wilfred Cude's book he wrote about his father, former Montreal Canadiens netminder of the 1930s, Wilf Cude.

The book's description is as follows:

Wilf Cude (1906-1968): gifted NHL goaltender, dedicated hockey coach, conscientious sports talent scout, small businessman, husband and parent. A hockey book with all the statistics and information any hockey enthusiast might want, it's a story of success, failure, strength, skill, determination, negotiation, love and luck. This offers a lively and spirited literary immersion into our Canadian and North American hockey past, as well as a son’s loving tribute to his famous father.

I had known Wilfred Cude Jr. through doing my Manitoba hockey research over the past five years or so. A noted scholar, Wilf Jr. taught English Literature at several universities across Canada. When I first met him, he was just in the finishing stages of completing this book.

He was able to fully complete the book shortly before he passed away in October of 2018 at the age of 80. Since he passed, I have worked with family and friends on getting the book published and in the hands of hockey fans across the world. I had a PDF version of the book that I always made sure I read once or twice a year since Wilf Jr. passed. The book is that good.

Anyways, since reaching out to one of Wilf Jr's siblings over the past few months, we were able to expedite the process and get Dear Red Light published via Amazon.

Dear Red Light is not your typical hockey history book, but instead a son's look into his father's life. One that I'm sure many people here will enjoy.

Dear Red Light can be purchased exclusively through Amazon at the link here.

I am here to try and answer any questions that anyone has! So please fire away.

And finally, here is an excerpt from the book's opening chapter:

One sharp cold night deep in the winter of 1955, late January maybe, or early February, I was out in the kitchen when somebody came knocking softly at our back door. When I opened the door, there was a smallish older guy standing there, dressed in a railway man’s outfit, Ontario Northland Railway, heavy overshoes, sturdy winter coat, official cap and all. In a slightly Québécois accent, he asked: “Excuse me please, but is Wilf Cude at home?” Inviting him to step inside, I went back into the living room where my father was stretched out on the sofa, snoozing as was his habit in an after-dinner nap. I shook him gently, and told him: “Dad, there’s someone to see you, out in the kitchen.” He pulled himself awake and stumbled off to welcome his visitor.

An explosion of greetings followed. Dad could be noisily demonstrative when he was greatly pleased, especially when encountering a friend from way back then, so I knew this had to be an old buddy from the hockey days. Funny thing, though, this one was rather smaller than most of the others who dropped by: he actually made my father look just a touch bigger, which didn’t happen often in those circles. Not that I cared much then. I was sixteen and a very keen Sea Cadet, determined to join the Navy as soon as I could, with every intention of becoming an Admiral in the fullness of time. An Admiral: the word comes from the Arabic amir al-bahr, Lord of the Sea, and the book I was reading upstairs in my room described the clash of such Lords of the Sea, Japanese and American at the battle of Midway. That was history, that was real, and that’s where I went in my imagination, to the clink of ice cubes in two glasses from the living room below.

Under the weather, I decided to try a sympathetic conversational gambit. “Dad,” I asked, “who was that little guy last night?” He looked at me with a vaguely quizzical glance I had long since learned to recognize, sort of a wonderment at how the question could have manifested itself. “That little guy, son,” he explained, speaking slowly and distinctly, “was Aurèle Joliat.” To which my response, I’m afraid, was nothing more than “Oh,” as I returned my attention to the bowl of porridge before me. Absolute impenetrable incomprehension emanating from me, silence all around descending, the conversation now (figuratively speaking) dead in the water, sunk as deep in the depths of my ignorance as were Admiral Nagumo’s four fleet carriers sent down deep under the oilslicked flaming Pacific waves off Midway, so long ago and far away from Noranda, Quebec. From our breakfast table, me in particularly studied silence, contemplating (and not for the last time) the unplumbed depths of my own incomprehension. My mother was smiling discreetly, my younger brothers Davey and Alan were busy with their own breakfasts, our older sister Beverley was away at college, and Dad was concentrating on getting his glass of tomato juice down. And so that day began for us, much as many others before or after.

Aurèle Joliat! One of the much more flamboyant Lords of the Hockey Arena! In my very own living room, sharing who knows what stories over a glass or two of toxic with my dad, and me upstairs shut away with a book, and not one sweet flipping clue about the import of the event below. Sports history slipping past me, unrecorded and lost forever, while I’m hopelessly insensitive and oblivious to it all. Aurèle Joliat! When he and Dad shared the ice, they were two of the smallest guys in the League. Aurèle at five feet, six inches and 135 pounds, with dad at five feet, eight inches and 133 pounds, they each had to be very fast, very agile and very tough, each in his own highly personalized way. Known as either “The Mighty Atom” or “The Little Giant,” Aurèle skated left wing for an astounding sixteen seasons with the Canadiens, a top scorer in every one save the last, and far taller and heavier opponents instantly and painfully learned not to mess with him. Swift, crafty and well adept at using his stick, in either regulation or unorthodox fashion, he could leave a belligerent wannabe thug sprawled flat on the ice behind him as he went on to twist the knife with yet another goal.

What a legend that ferociously diminutive left-winger soon became. Immediately recognizable as he skated into position wearing his jaunty trademark slightly peaked cap, he was on his way from the outset into the Hockey Hall of Fame, only the third among the first ever Canadiens to arrive there. His lifetime score of 270 goals endured as a team record until finally surpassed by Maurice Richard in the 1951-52 season, and he is still ranked ninth on the team’s current overall list of top scorers. He was instrumental in taking the Canadiens to the League championship three times, in 1923-24, 1929-30 and 1931-32. He won the Hart Trophy as the League’s most valuable player in 1933-1934, and continued as a potent force until his retirement at the close of the 1937-38 season. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1947, soon after the Hall was opened, following close behind his teammate Howie Morenz, himself one of the initial twelve inductees in 1945.